Mental Traveler: A Father, A Son, And A Journey Through Schizophrenia

How does a parent make sense of a child’s severe mental illness? How does a father meet the daily challenges of caring for his gifted but delusional son, while seeking to overcome the stigma of madness and the limits of psychiatry? W. J. T. Mitchell’s memoir tells the story—at once read more

Preface:

1. “I Need to Become Homeless”

2. A MAD Tour

3. The Therapeutic Landscape

4. “There’s Something in My Head”

5. From Desolation to Da Jewels

6. Flying and Falling

7. Diagnoses and Detours

8. “He Killed the Future”

9. He Was Too Strong for His Own Good

10. Gabe’s Back Pages

11. Philmworx

12. The Immoral Career of the Caregiver

13. On the Case of Gabriel Mitchell

Postscript Poems by Janice Misurell-Mitchell

Gabriel’s Email to the Family, on Grammy’s Death

Acknowledgments

Further Reading and Viewing

Mental Traveler Reading, Seminary Coop Nov 18 2020

Mental Traveler Reading, Seminary Coop Nov 18 2020, Lauren Berlant, moderator

WJT Mitchell, reading Mental Traveler at Bookcellar

Let’s Talk About It, Interview with Vineesha Arora Sarin

LET’S TALK ABOUT IT – EPISODE 4 – Vineesha with Carmen E. Mitchell & W.J.T. Mitchell

Mental Traveler chapter nine, excerpted

THE FOLLOWING IS an excerpt from W. J. T. Mitchell’s Mental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey Through Schizophrenia, a memoir about Mitchell’s son Gabriel, who struggled with schizophrenia for 20 years until his suicide at age 38. The excerpt makes reference to Carmen, Gabriel’s sister, a filmmaker based in Los Angeles, who is currently at work on a film about her brother, shot through the lens of his own film footage and artwork. Mental Traveler was published by The University of Chicago Press in September.

One of the common features of schizophrenia in gifted individuals is a belief that the illness can be conquered with strength of will. The portrayal of the mathematician John Nash in the film A Beautiful Mind exemplifies this notion, treating Nash’s “recovery” from madness as a simple matter of deciding not to believe in the reality of his own hallucinations. He tells his imaginary friends to go away, and they fade into the background. A more nuanced account is provided by Elyn Saks in her autobiography, The Center Cannot Hold. The most important delusion that Saks has to overcome is her feeling that she can simply reason her way out of her condition: “I thought that if I could figure it out, I could conquer it. My problem was not that I was crazy; it was that I was weak.”

It is the oldest cliché of psychology. Denial that one has a problem is the first and hardest problem to overcome. Like the Protestant doctrine of “conviction of sin,” the acknowledgment of one’s own sinfulness and need for grace, the acceptance of a diagnosis or, at a minimum, the acceptance that one needs a diagnosis, that there is a problem in one’s life that cannot be wished or willed away, is a precondition for successful treatment. And “success” can be a very complex matter, since the idea of normality and mental health is at least as vague and contradictory as the idea of madness. In the case of schizophrenia, sometimes the best notion of success is to accept one’s condition as incurable but treatable and survivable. When Saks accepted that she would need to be continuously alert to stress, vigilant to spotting warning signs and situations (e.g., the moment of changing therapists), her life became a matter of managing schizophrenia rather than of overcoming it. When she understood that the need for medication would probably never go away, she was well on the road to what would count as a successful life. When Aby Warburg, the German historian of art and culture, emerged from his five-year confinement in a mental hospital, he defined his own condition as that of a “revenant” or ghost, an “incurable” who had found a way back into the world for an afterlife. When Judge Schreber, the mad jurist who served as the most famous exemplar of schizophrenia in modern Europe, fought to be released from his confinement, it is his writing and legal reasoning that does the trick; his elaborate system of delusions survived intact and became the mythic core for the most famous first-person account of madness in the 20th century.

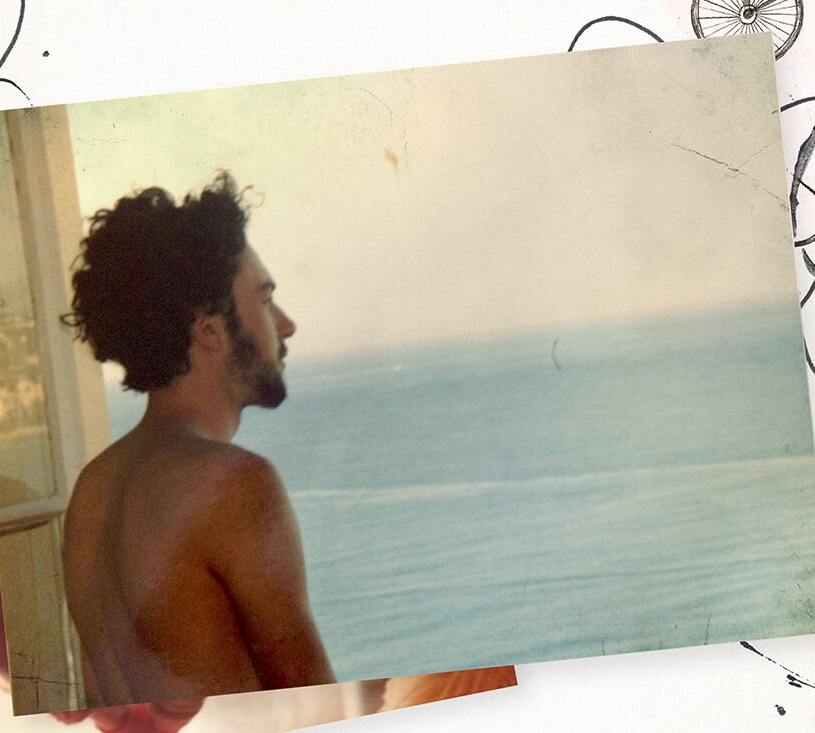

Gabriel was too strong for his own good. His therapists all testified to his ability to “present well,” as the jargon puts it. He did not fit the stereotypical image of schizophrenia as withdrawn, angry, delusional, obsessive, and all-around difficult. He saved that mostly for us. His personal grooming was excellent. He defied the tendency of medications to induce obesity by working out energetically, cycling, skateboarding, stair climbing, and going to the gym. His apartment was generally quite neat, with books, tapes, and DVDs arranged logically. His desk was carefully ordered with drafting tools and materials ready to hand. Of course, the whole space always reeked of tobacco, the most widely used self-medication for schizophrenia.

Being a social butterfly is not part of the stereotype of schizophrenia. At art openings, house parties, and receptions, Gabe would work the room like a skilled politician, meeting new people and engaging them in conversation and handing out his business cards. There was not a trace of cynicism or opportunism in this behavior. Live encounters with the outer faces and voices of others helped to push away the destructive inner voices that plagued him. In spite of his empathetic, sociable nature, however, he felt terribly alone in the world and complained bitterly when people failed to show up for appointments or canceled at the last minute. Probably they were oblivious to the hurt they were inflicting. After his death, scores of people came forward and testified about memorable encounters with him in which they glimpsed his empathy and sensitivity (the most frequent adjectives that come up in these anecdotes are “sweetness,” “enthusiasm,” “brilliance,” and “openness”). One of his dear friends who suffered from depression remarked about a day with him: “Our conversation made a before and after of that day for me. Afterward, we determined that our respective insurance companies should pay us for providing each other with therapy, and we also determined that I needed to get dance shoes.” He could segue from small talk to the meaning of life without missing a beat.

Many people who knew Gabe were completely unaware that he had a mental illness, and his darkest episodes were mostly confined to intimate family situations, where his anger and despair and grandiosity could flourish openly. But even within the family, he tended to conceal the depth of his suffering. When I asked about how he was feeling, I was generally rebuffed with the retort “How are you feeling?” When I would ask if he was having nightmares, he would often turn the question aside or, conversely, assert that they were stronger than ever, and then to go on to describe nightly dreams of being torn apart and devoured by insects, visions worthy of Bosch’s lurid portrayals of the torments of hell.

I think he was engaged in a double defense mechanism: defending himself against having to open up the Pandora’s box full of demons that were plaguing him, while also defending us against the intensity of his pain and reassuring us that all was well. He consistently refused to engage in serious talk therapy, even after he had come reluctantly to accept the need for medication. He preferred the passive “Rogerian” style of therapy, in which he could filibuster for the entire hour without being challenged by the therapist, whose only role was to periodically murmur “mm-hmm.” And he expressed mixed feelings about this technique, sometimes mocking it quite savagely by imitating the bland clichés of professional “concern” (“And how are you feeling today?” “And how did you feel about that?”). At other times, he was willing to admit that it might be of limited benefit, and he had no problem with talking about himself. When he was asked if he ever had thoughts about suicide, he emphatically denied it, assuring us and his doctors that he would never do anything like that.

At the same time, his screenplays were projecting images of himself both as a superhero capable of amazing feats of intellectual and physical strength, and as the victim of dark forces, betrayal, and persecution. In one screenplay, The Politics of Dreams, he divided the character of his alter egos in two. On one side is Abby, a famous Hollywood director and actor who is about to receive an Academy Award for lifetime achievement; at the same time, he is completing his magnum opus, Quantum Geometrics: A Unified Physics of Peace. On the other is George, a failed screenwriter who is “a paranoid, delusional psychotic” and a drug fiend. George hates Abby for his success and for his bad taste in films. He is outraged that Abby regards Casablanca as a better film than Citizen Kane. Abby represents the “industrial” model of cinema as mass culture, while George is portrayed as the frustrated auteur who identifies with Orson Welles. If Abby is a projection of Gabe’s grandiose ambitions, George is a portrayal of his actual suffering, beset by hideous nightmares and voices urging him to commit suicide. George tries to assassinate Abby as he walks the red carpet at the Oscars, succeeding in leaving Abby in a coma.

The interesting plot twist in The Politics of Dreams occurs when Abby awakens from his coma, decides to forgive his assassin, and invites him to spend time with him in his hospital room. George is brought in wearing a straitjacket, and together they watch a retrospective of all the films in Abby’s long career. The films comprise every genre known to Hollywood — Western, science fiction, noir, psychological thriller, courtroom drama, boxing, dinosaurs, crime procedural, war, even a picaresque biker film modeled on Easy Rider. Every film has a “Hollywood ending,” with Abby as a cowboy, astronaut, detective, scientist, or Christ figure who always gets the girl and saves the world. George is completely contemptuous of Abby’s success, insisting that these formulaic films are trashy productions for the commercial culture industry. He then reveals that he himself is a screenwriter — “My scripts are about real things, not some dream factory” — and gets a lecture from Abby on how to pander to audiences to have a successful film career.

While this retrospective is unfolding, George is busy wriggling his way out of his straitjacket so that he can finish Abby off. He frees himself, strangles Abby (who will later be resuscitated, of course, in Hollywood-ending style), and escapes from the hospital, cutting off his own legs to free himself from his shackles. After a long, legless crawl through sewers, George winds up dead in a crack house and is taken to the morgue. But there, a small miracle occurs: a “mysterious house fly crawls out from George’s hair,” an escape hatch opens in the middle of George’s lifeless brow, and a miniature version of George crawls out and mounts the fly, which takes off like “a little Pegasus” to fly back to Abby. George becomes Abby’s invisible companion, riding on his shoulder like a familiar spirit or incubus. The screenplay ends with Abby delivering a eulogy at George’s graveside, as the fly takes off with the miniature George “riding like a cowboy … directly into an electric bug zapper,” where they are “fried instantly.”

I read now about Abby and his evil alter ego, George, and I peer cautiously at Gabe’s delusions of grandeur and the actuality of his suffering — which, in a sense, fought each other to a draw. It is as if Gabe turned the psychoanalytic dialogue into a debate about cinema, rendered as cinema — or at least as screenplay. The talking cure becomes the screenwriter’s dilemma, providing illusions for the masses, or unwelcome and unmarketable glimpses of the realities that lead the screenwriter into the grave. Gabe and I once discussed the idea of an entire seminar on “back lot” films (the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard were among our favorites). The Politics of Dreams, which incorporates all the genres of cinema, is itself meta-cinema.

When Gabe would visit Carmen in Los Angeles, he would mingle with her circle of friends, including actors, directors, technical people, and, of course, screenwriters. Carmen was writing and acting in plays herself, while holding down a day job at the Writers Guild. As in the academic world, where everyone has his or her book project, in Hollywood, nearly everyone has a script tucked under their arm. The conversation inevitably turns to the question of how one can “take a meeting” with an insider who will open the door to a contract and the ensuing fame and fortune. It is a political field of dreams in which delusions of grandeur are almost completely normal. Carmen noted that Gabe’s fantasies fit right into the collective psychosis of aspiring workers in the dream industry.

Gabriel’s last words to me on the phone the day of his death were an accusation: “You have never read my screenplays.” Of course, I instantly denied this, but there was a terrible, haunting truth to the charge. I think I was incapable of reading his scripts the way I do now, now that they are posthumous records of his struggle. Then I was reading them as a father and caregiver in relation to the ongoing life of my son. Now I read them in a way that I find much more difficult to classify. Is it an act of mourning, of penance for failing to give him the reading he needed when he was alive? Or am I now free to “do a reading” of the sort that I do as a scholar, linking them to other cases of visionary testimony offered by gifted schizophrenics? Am I reading them to understand him, or his illness? Or in search of something well beyond illness?

When Gabe showed me The Politics of Dreams, I was, of course, disturbed by the terrifying figure of George and annoyed by the grandiose projection of Abby the Great, both expressing aspects of Gabe’s self-image — or perhaps a caricature of his successful father. I suppose I gave the screenplay a merely symptomatic reading, which in a way is not to read at all but to know beforehand what a text means, to search it for confirmation of a diagnosis — what Kenneth Koch used to call “being the dermatologist at the birthday party,” when he admonished us against reading poems this way. I think we all fight this impulse as readers. Most perplexing is the fact that reading someone’s writing or listening to them speak “as symptomatic” can be deeply disrespectful, like the incompetent psychoanalyst who tells a patient, “That is just your psychotic grandiosity talking.” The worst thing one can say to someone having a psychotic break is “You are having a psychotic break.” Of course, since it may also be the only true thing that it is possible to say, silence, lying, and evasion are what one usually resorts to. Beyond that, a symptomatic reading strikes me as too quick to impose closure and apply labels; for example, this is (nothing but) a symptom of schizophrenia. Where is the line between symptom and sympathy? I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now.

And of course there were questions about the viability of Gabe’s scripts as steps toward a career as a screenwriter. I cringe to recall how evasive I had to be when he insisted that I endorse and transmit his scripts to my old friend Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. (Skip is known to the world as the Harvard professor who directs the television series Finding Your Roots, but he also appears as a prominent character in Gabe’s script for The Politics of Dreams, playing Abby’s best friend and director.) Skip wrote Gabe an encouraging letter, which he cherished. But Gabe became obsessed with the idea that Skip and I could get Spike Lee to “take a meeting” that would lead to fame and fortune. Anyone who has spent time in Hollywood knows that the idea of “taking a meeting” with an influential player is the Holy Grail of “the industry.” Skip tried to let Gabe down easy by telling him, “Gabe, even I can’t get Spike to return my calls.” He urged Gabe to continue his education in filmmaking and prepare himself to be ready when his moment would come.

I did not get off so easily. I had met Lee briefly in the fall of 2000, when we were on a panel together to discuss the recent release of his film Bamboozled. So of course Gabe expected me to call the great director and arrange a meeting. Why wasn’t I doing it? Why was I blocking his career when, as his father, I should have been helping him achieve his hopes and dreams?

Nevertheless, Gabe and I could share our love for Lee’s film, and we watched Bamboozled together many times. He immediately added it to his list of films about screenwriters — in this case, a film about a television writer who produces the script for a “New Millennium Minstrel Show” that violates every racial taboo known to American culture. Is the screenwriter, Pierre Delacroix, a victim of the “idiot box” that corrupts his talent? Is he a yuppie sellout, an “Oreo” (black on the outside, white on the inside) who will do anything to preserve his cushy lifestyle and his daily Pilates classes? Or is he going insane, his immersion in the racist stereotypes of “Sambo Art” turning into a psychosis that makes the mechanical dolls of Aunt Jemima and Stepin Fetchit come alive? Gabe lived inside this film and took me there with him. And he brought Spike and Skip into supporting roles in his own fantasy world of a brilliant Hollywood career.

Now I try to read his scripts differently, in a way that can only happen when the text is the testimony of someone who has crossed the threshold into madness and death, and left a compelling story about it, along with an unfinished project of understanding. I can no longer bear the symptomatic readings, which confidently label these writings as expressions of this or that syndrome. Who gives a damn whether they are the results of a bipolar disorder or schizophrenia? Like Elyn Saks, Aby Warburg, and William Blake, Gabe lived on the border of a world that most of us know only fleetingly — a world of suffering and shattering both relieved and exacerbated by grandiose fantasies, expressed by a fierce determination to put those fantasies to work and build a world out of the ruins. He was a mental traveler.

“The Caregivers Dilemma,” interview with Benjamin Kafka

W. J. T. MITCHELL is one of the most influential academics of the last three or four decades. As a theorist, he helped transform how we understand the power of images to shape our selves and our worlds. As editor of the journal Critical Inquiry, he oversaw the emergence of many of the great interdisciplinary movements that revolutionized the humanities starting in the late 1970s.

Many of us who have admired him from afar had no idea that all this work was taking place against a background of immense personal suffering. In the fall of 1991, his son Gabriel, then a freshman at NYU, experienced a psychotic break, which took the form of a sudden, overpowering need to become homeless. Over the months and years that followed, Gabe would retreat more and more into madness — diagnosed, for the most part, as schizophrenia. This struggle ended, in 2012, with Gabe’s suicide.

Or, rather, the struggle has continued, now differently, as the painful work of mourning. Mitchell’s new book, Mental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey through Schizophrenia, recounts the impact of Gabe’s illness on Mitchell and his family. The book is brief, matter-of-fact, and agonizing. I suspect that many who read it will identify with one or another of the people we meet there, all of whom are doing their very best under very difficult circumstances: the desperate parents, the distraught sister, the worried friends, the ineffectual mental health professionals, and of course Gabe himself, whose belief in his own greatness was so in tension with the reality of his situation.

One of the great virtues of Mitchell’s book is its honesty about the challenges of caring for someone who moves in and out of states of grandiosity. The British psychoanalyst Eric Brenman used to say that, in madness, you can be both Jesus or Napoleon and a very small child whose needs must be met by others. In these grandiose states, the needy part of the self is a despised part of the self, hence the impulse to experience it as if it were outside the self, something foreign and dangerous. In some delusions of persecution this takes the form of individuals or organizations that are trying to rob the self of its extraordinary powers, usually out of greed or envy. In other delusions, the enemy takes the form of invisible, or only dimly visible, social forces, though the motives and methods remain much the same. Gabe seems to have found confirmation for the latter delusion in the anti-psychiatric literature: R. D. Laing, Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari, and similar authors who encourage us to see schizophrenia as a political phenomenon rather than as a sickness. Tragically, it is both.

“I want to put my illness to work,” Gabe tells his father at one point. “My goal is to transform schizophrenia from a death sentence into a learning experience.” Tragically, here, too, it is both. Mitchell’s book carries that work on, making it possible for all of us learn from Gabe’s experience as well as his own. Mitchell and I spoke over Zoom about the Mental Traveler last month. A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

BEN KAFKA: Thank you for agreeing to speak with me.

W. J. T. MITCHELL: As you may have noticed, I love talking about my son. I loved him dearly, and I thought he was an extraordinary person, so I’m always happy to talk about him. People always say, “It must be hard for you to talk about this.” I say, “Actually, no. It’s really good.”

Is that part of what moved you to write this book?

The basic motive maybe, I’ll never know. I felt I owed it to him, that I had a debt, that he had these wonderful ambitions that weren’t fulfilled, couldn’t be fulfilled, and that I thought could and should have been fulfilled if he had survived. So I wanted to give him some measure of what he wanted.

I also felt like I had to tell his story. As I say at the beginning of the book, there are some books you want to write, and there are other books you have to write and you never thought you would. I didn’t expect to do this, but I actually started writing it the day after Gabriel died. The first draft was completely different. It was terrible. It was defensive, an apology for writing this and for having to write it. I showed it to one of my closest friends, Bill Ayers, and he said, “Tom, this isn’t what you want to say. Don’t apologize, just tell his story.” Bill simply gave me permission to narrate.

Some of the things that are in the book now came in very late. The first things that I wanted to talk about were the things that made it clear, in memory and to a reader, why [Gabriel] was an extraordinarily lovable person. Parents love their children, but I wanted to specify it. What was lovable about him?

Many things come across powerfully in the book, but one thing that came across with particular force was the energy inside Gabe. There was clearly a kind of movement inside him all of the time.

He was a person with great ambitions as a filmmaker. I think this sometimes got the unfortunate label of “grandiosity.” I found myself warning him against grandiosity. “Be realistic.” I regret every time I said that, because it became an issue for him. “Oh, am I being grandiose now?” I don’t know what the right thing to say is when someone is going way overboard with their ambitions. Just as an example, he had a video camera, a Handycam, which we gave him, and he was constantly using it, constantly making movies. But he said, “The proportions of the image have to be for Cinemascope.” [Laughs.] I asked why, and he said. “Because when all of this is being seen on the big silver screen, it’ll need to be in Cinemascope. I don’t want to have to reshoot it all.” So yeah, he had a tremendous energy, but also tremendous blockages for it as well.

So much of the book is about the movies.

Yes, it really is. He was destined to be a moviemaker. He was constantly shooting films and finishing a number of them. Not to mention all of the scripts that he wrote, and he studied film history.

What struck me, both in reading the book and in watching some of Gabe’s movies online, is his desire to get at some kind of truth, and his deep impulse to communicate it, to share it with others.

When it came to film and talking about it, that’s where he was very communicative. If you tried to talk to him about the voices he was hearing, about his illness, he became very defensive. A lot of people didn’t understand that he had a mental illness because he would present so well. But we knew because of the anger, the frustration, the unhappiness he would pour out to us. Even with us, though, he became more and more defensive, I think. The worse he felt, the more he felt he had to protect us from it, or that it would just be bad to talk about it. He never could open up to a therapist fully. I mean, he would talk, but as he’d describe it, “I filibustered for an hour, I blustered, bullshitted them. Because they can’t help me. They don’t know what they’re dealing with.”

I guess talking can be a way of getting at the truth but also of getting away from the truth. And Gabe was bright enough to do both well.

He was very good at evasive action. He was a complex and gifted person. There was an unexpected turn in the last few years, where I was starting to be his student. I was learning from him and trying to catch up with him. Partly because, as his interest in film grew and he became more ambitious about it, he wanted to pull me into it. I wanted to be pulled into it, and in fact I was pulled into his project for a nine-hour film that would show “madness from inside and outside.” It was an Histoire de la folie modeled on Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma. I became his research assistant, charged with assembling a global archive of images of madness, a “Bilderatlas” of insanity. The remains of that project will be my next book.

But probably my biggest decision was whether to retire from my academic job and go into the film business as his partner. But then, I’d think, no — that’s a bad idea. I was afraid that it could be really bad for him for me to be too involved. That’s why the decision about making films with him was so agonizing. I still have second thoughts about it. Perhaps this is why I’ve been watching lately lots of films about time machines, which all deal with the question of whether you could go back to a decision, take the other choice, and see if that worked out. What would an alternate history look like in which things did not go this way?

One feature of having someone in your family who’s suffering the way Gabe suffered is that you really just don’t know what to do. You don’t know what the right choices are. You feel like every choice is a wrong choice. And in some ways, every choice is a wrong choice.

That is the great dilemma of what they call the “caregiver.” It does seem like there are no good choices, except sort of being there, being sympathetic, and trying to hold it together. But to be proactive, to try to push in some direction or other, can be full of peril.

The major decision we had to make, very early on, was whether he should live with us. And we decided, and his therapists agreed, that it was bad for him to live with us. Of course, his perception of that, when he was angry was, “You’re throwing me out, aren’t you? You don’t want me around because look at the mess you made of me.” And we’d say, “No, no, we love you very much, but it’s not good for you to be here. You have to grow up; you have to be independent; you have to set your own course in life.” So you have these kind of impossible conversations. But, of course, the fact that you have been urging him to go into the mental health system, where he’s being labeled and diagnosed, most traumatically with schizophrenia, he says, “You’re throwing me out and you’re putting a label on me that makes me an outcast. And you’re collaborating in that exile of me from straight society.” His greatest fear was being cast out. That’s what schizophrenia is: you are cast out.

You’ve probably observed this in your own practice. Families don’t always agree about the right thing to do when someone goes crazy. And, as you said, sometimes there is no right thing. But you have to decide on something. And then when that becomes mixed up with family dynamics, it can become very toxic, dangerous for a family unit. People second-guessing each other.

In a way, it drives all of us mad, doesn’t it?

It’s contagious. You feel like, what are we supposed to do here? How are we supposed to understand this? What’s the reasonable and rational thing to do?

So let’s talk a bit about your work of understanding. You said you began to write the book immediately after his death, so that was —

2012.

Eight years, almost a decade ago now. The book attests to your own long work of trying to make sense of Gabe, of his schizophrenia, of his death.

I’m not a psychiatrist. I don’t have any competence with these labels. But as a parent, I had to struggle with the labels. Gabe and I were also doing a reading program about schizophrenia from many different angles. E. Fuller Torrey’s Surviving Schizophrenia to the rescue! And Elyn Saks’s wonderful memoir of her life, The Center Cannot Hold, which Gabe and I actually read together.

What was that like, reading those books together?

I think the most exciting thing was when we started reading the anti-psychiatry movement together. We read R. D. Laing and Deleuze. And that’s when he began to turn it into a political issue, and to identify himself as part of a minority. He also started to treat madness, mental disorders, as a collective phenomenon. He would have thoroughly approved of an essay I wrote about the Trump election called “American Psychosis,” (published in the LARB, by the way), about how an entire country can go crazy. Whether that’s a clinical issue is another question, but there’s no doubt that something irrational, self-destructive, deeply deluded has overtaken American culture. He was very happy to make it a political issue. It made him feel better, in a way, to say, “I’m not actually cast out. I’m just a more sensitive seismograph of the craziness that is all around.”

There’s a tension in the book, and I think a tension in a lot of people’s experiences, between, on the one hand, this very private experience of madness — some of which can be shared, and some of which, for the schizophrenic, can never be — and on the other hand, madness as a sort of social, cultural, political phenomenon.

Yeah, we were really caught in it. Because on the one hand, I wanted him to be cured. I wanted the suffering to be alleviated. He was tormented. And of course the love story is central to that. When we read R. D. Laing’s The Politics of Experience and came to that passage where Laing says, essentially, forget about the modern labels, maybe schizophrenia is fundamentally a broken heart and a shattered self. We said, “That’s it!”

When Gabe was a freshman at NYU, he became obsessed with a young woman who was oblivious to the effect she was having on him. We met her a number of times. And they were never boyfriend and girlfriend, but she was the kind of young woman who could say, “Oh, I adore Gabe. He’s such a wonderful guy. I do love him.” And we would say, “Okay, you can tell us that, but don’t say that to him.” He didn’t know how to hear that without taking it in a way that she didn’t intend. “You are supposed to be his life partner, that’s what he feels. You are the key to his entire destiny.” A lot of his suffering was just unrequited love. He idealized this young woman and made her the center of his being. That went on until really very late. It never completely disappeared.

Then there his alternate narrative of his illness as PTSD. He believed that all of it had been the result of a single trauma, of being hit over the head with a tire iron, of being beaten up in a gang rumble downtown, a story we could never verify, but which he could elaborate with lurid details of betrayals by his friends.

And then the third narrative of his schizophrenia as a kind of social or political phenomenon. Your book argues that society has come up with a system for diagnosing or classifying people, who often end up feeling cast out …

Yes, and the casting out as being the most important thing. We went through the predictable cycle of labels, usually with a sense of relief that his condition had a name, and then disappointment when that name turned out not to include a cure. Even after his passing, I’ve had psychiatrists tell me with full confidence, “Everything you’re telling me suggests that he was bipolar, not schizophrenic.” When they say that, I get pretty pissed off. For one thing, you’re saying that on the basis of hearing my random remarks, you’ve never talked to him yourself. And besides, what difference would that make?

[Long pause.] Ben, have you been doing therapy on Zoom?

No. I only use the phone. I think, when we first had to start deciding how to continue working, there was this idea that video sessions would somehow be closer to in-person treatment, but if there’s one thing we media theorists know, it’s that this is an illusion. Also I just don’t like it.

Is it the face-to-face? Is that the problem?

The digital artifacts give it an uncanny feeling. The pixelation, the brief delays, the mismatch between sound and image. Not that the phone is great, especially the cell phone, but for me at least the phone marks a difference. Like, this is not a normal time, this is an unusual time, and we’re doing something different until we can go back to doing what we’ve been doing.

And then of course there’s the question of, “Could this be the new normal? Are we going to have to adapt?”

Most of my patients lie on the couch, so it’s not face-to-face anyway, though obviously the physical proximity, with all of its pleasures and anxieties, is an essential part of the experience.

I’m deeply in love with Freud, I don’t care what anybody says.

Who’s not in love with Freud?

Our young students, for one. They tend to dismiss Freud as hopelessly out of date, sexist and clueless about modern problems. That is why when I have taught, for instance, Freud’s case history of Dora, I don’t try to convince them that he understands Dora, or that he did the right thing, or anything like that. Of course it’s a failed analysis. But I divide the class in two, and ask half of them to mount a defense of Freud. Invariably, the defenders do the better job, because they have to work hard to overcome their contemporaries’ automatic prejudices.

You know, I think that there’s something about Dora, something about early Freud in general, that’s relevant to what we were talking about earlier, about family dynamics, group dynamics. So much of that treatment consists of Freud trying to get Dora to listen to reason, or what he thinks of as reason. It’s like he’s shaking her by the shoulders shouting, “Can’t you just be reasonable?” But of course she can’t be reasonable, her situation is crazy, it’s made her crazy, he’s making her even crazier, and soon she’s making him crazy as well. He keeps insisting and insisting until finally she says, “Fuck that,” and off she goes. It’s the only sane moment in the treatment. As we know, Freud then spends a number of years brooding over it and decides to publish this record of his failure and what he learned from it, which is the theory of transference, which implies that at some level we can never “just be reasonable” with one another.

I think that those of us who have spent time with madness in its many forms, in any of its forms, can relate to Freud’s attitude, as problematic as it is. On the one hand, I know that you’re going through something crazy, that you can’t just be reasonable. On the other hand, we still sometimes find ourselves insisting, Why can’t you just be reasonable?

That’s right. And Freud had the honesty to write it all down, and not to give himself the credit for any kind of cure, but to describe it for what it was: a failed analysis.

Did you have moments like that, of can’t you just be reasonable? with Gabe?

All the time. But then I’d think, “How reasonable can I be? What are my reasons here?” The line between mental illness and normality, the more we experienced it, the way we studied it together, it just seemed to slip into so many gray areas. Even the fairly clear line between neurosis and psychosis — the line that served as the boundary between where I am coming from psychologically and where he was — even that tends to fray sometimes.

It does seem that in a lot of the anti-psychiatric literature — and I can see Anti-Oedipus over your shoulder there in the background — there’s something that tends to kind of wish away the madness of madness, the terror that Gabe was experiencing, the terror that you, your wife, and your daughter were experiencing. There’s something about the romanticization, even celebration of schizophrenia in Anti-Oedipus that leaves all of that behind.

It was a real temptation for both of us. And this is probably, for me, a result of my early work. My doctoral dissertation was on William Blake, and though psychosis wouldn’t be the right name for his mental condition, he had visions, he heard voices. His poems were dictated to him, and he said he was “copying his imagination,” his visions of what would appear to him. But Blake’s madness was in a religious, artistic, and political context completely outside of any clinical framework. All he had was hostile reviewers who would say, “This guy is crazy … he would be confined as a madman except that he’s harmless.” Madness itself is, as we say, a historical construction — it’s treated in radically different ways with different language around it, and it’s constantly evolving. The DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders] is itself evolving — and growing ever larger.

Gabe’s suffering with schizophrenia, most of all, was feeling isolated by it. And that terrible feeling of watching your friends grow up. The people you were kids with: they get married; they have a job; they have a profession. And he kept saying, “When’s my life going to start?” As if we could say, “Here, get started. Now you can do it.” That was some of the hardest stuff to deal with.

These are hard circumstances, but it’s been a pleasure speaking with you.

Well, it’s like I said, I don’t mind talking about this at all. It’s one of my favorite things really. If anybody wants to know anything about my son, I’m ready to talk about him because he was my hero. A hero of my own story and his.

W.J.T. Mitchell, in conversation with Bill Ayers, discusses Mental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey Through Schizophrenia

How does a parent make sense of a child’s severe mental illness? How does a father meet the daily challenges of caring for his gifted but delusional son, while seeking to overcome the stigma of madness and the limits of psychiatry? W. J. T. Mitchell’s memoir tells the story–at once representative and unique–of one family’s encounter with mental illness and bears witness to the life of the talented young man who was his son. Gabriel Mitchell was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age twenty-one and died by suicide eighteen years later. He left behind a remarkable archive of creative work and a father determined to honor his son’s attempts to conquer his own illness. Before his death, Gabe had been working on a film that would show madness from inside and out, as media stereotype and spectacle, symptom and stigma, malady and minority status, disability and gateway to insight. He was convinced that madness is an extreme form of subjective experience that we all endure at some point in our lives, whether in moments of ecstasy or melancholy, or in the enduring trauma of a broken heart. Gabe’s declared ambition was to transform schizophrenia from a death sentence to a learning experience, and madness from a curse to a critical perspective.

Shot through with love and pain, Mental Traveler shows how Gabe drew his father into his quest for enlightenment within madness. It is a book that will touch anyone struggling to cope with mental illness, and especially for parents and caregivers of those caught in its grasp. (University of Chicago Press)

Event date:

Thursday, September 17, 2020 – 6:00pm

Event address:

Mental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey through Schizophrenia (Hardcover)

By W. J. T. Mitchell

$22.50

ISBN: 9780226695938

Availability: On Our Shelves Now

Published: University of Chicago Press – September 1st, 2020

Top of Form

Add to Cart Add to Wish List

CONTACT